History as Trajectory

Chapter 2

Prologue

Narrated by Balaji AI.

Our history is the prologue to the network state.

This is not obvious. Founding a startup society as we’ve described it seems to be about growing a community, writing code, crowdfunding land, and eventually attaining the diplomatic recognition to become a network state. What does history have to do with anything?

The short version is that if a tech company is about technological innovation first, and company culture second, a startup society is the reverse. It’s about community culture first, and technological innovation second. And while innovating on technology means forecasting the future, innovating on culture means probing the past.

But why? Well, for a tech company like SpaceX you start with time-invariant laws of physics extracted from data, laws that tell you how atoms collide and interact with each other. The study of these laws allows you to do something that has never been done before, seemingly proving that history doesn’t matter. But the subtlety is that these laws of physics encode in highly compressed form the results of innumerable scientific experiments. You are learning from human experience rather than trying to re-derive physical law from scratch. To touch Mars, we stand on the shoulders of giants.

For a startup society, we don’t yet have eternal mathematical laws for society.8 History is the closest thing we have to a physics of humanity. It furnishes many accounts of how human actors collide and interact with each other. The right course of historical study encodes, in compressed form, the results of innumerable social experiments. You can learn from human experience rather than re-deriving societal law from scratch. Learn some history, so as not to repeat it.

That’s a theoretical argument. An observational argument is that we know that the technological innovation of the Renaissance began by rediscovering history. And we know that the Founding Fathers cared deeply about history. In both cases, they stepped forward by drawing from the past. So if you’re a technologist looking to blaze a trail with a new startup society, that establishes plausibility for why historical study is important.

The logistical argument is perhaps the most compelling. Think about how much easier it is to use an iPhone than it was to build Apple from scratch. To consume you can just click a button, but to produce it’s necessary to know something about how companies are built. Similarly, it’s one thing to operate as a mere citizen of a pre-built country, and quite another thing to create one from scratch. To build a new society, it’d be helpful to have some knowledge of how countries were built in the first place, the logistics of the process. And this again brings us into the domain of history.

Why History is Crucial

You can’t really learn something without using it. One day of immersion with a new language beats weeks of book learning. One day of trying to build something with a programming language beats weeks of theory, too.

In the same way, the history we teach is an applied history: a crucial tool for both the prospective president of a startup society9 and for their citizens, shareholders, and staff. It’s something you’ll use on a daily basis. Why?

-

History is how you win the argument. Think about the 1619 Project, or the grievance studies departments at universities, or even a newspaper “profile” of some unfortunate. You might be mining cryptocurrency, but the folks behind such things are mining history. That is, many thousands of people are engaged full time in “offense archaeology,” the excavation of the recent and distant past for some useful incident they can write up to further demoralize their political opposition. This is the scholarly version of going through someone’s old tweets. It’s weaponized history, history as opposition research. You simply can’t win an argument against such people on pure logic alone; you need facts, so you need history.

-

History determines legality. We denote the exponential improvement in transistor density over the postwar period by Moore’s law. We describe the exponential decline in pharmaceutical R&D efficiency during the same period as Eroom’s law — as Moore’s law in reverse. That is, over the last several decades, the FDA somehow presided over an enormous hike in the costs of drug development even as our computers and our knowledge of the human genome vastly improved. Similar phenomena can be observed in energy (where energy production has stagnated), in aviation (where top speeds have topped out), and in construction (where we build slower today than we did seventy years ago).

Obviously, even articulating Eroom’s law requires detailed knowledge of history, knowledge of how things used to be. Less obviously, if we want to change Eroom’s law, if we want to innovate in the physical world again, we’ll need history too.

The reason is that behind every FDA is a thalidomide, just as behind every TSA there’s a 9/11 and behind every Sarbanes-Oxley is an Enron. Regulation is dull, but the incidents that lead to regulation are anything but dull.

This history is used to defend ancient regulations; if you change them, people will die! As such, to legalize physical innovation you’ll need to become a counter-historian. Only when you understand the legitimating history of regulatory agencies better than their proponents do can you build a superior alternative: a new regulatory paradigm capable of addressing both the abuses of the American regulatory state and the abuses they claim to prevent.

-

History determines morality. Religions start with history lessons. You might think of these as made-up histories, but they’re histories all the same. Tales of the distant past, fictionalized or not, that describe how humans once behaved - and how they should have behaved. There’s a moral to these stories.

Political doctrines are based on history lessons too. They’re how the establishment justifies itself. The mechanism for propagating these history lessons is the establishment newspaper, wherein most articles aren’t really about true-or-false, but good-and-bad. Try it yourself. Just by glancing at a headline from any establishment outlet, you can instantly apprehend its moral lesson: x-ism is bad, our system of government is good, tech founders are bad, and so on. And if you poke one level deeper, if you ask why any of these things is good or bad, you’ll again get a history lesson. Because why is x-ism bad? Well, let me educate you on some history…

The installation of these moral premises is a zero-sum game. There’s only room for so many moral lessons in one society, because a brain’s capacity for moral computation is limited. So you get a totally different society if 99% of people allocate their limited moral memory to principles like “hard work good, meritocracy good, envy bad, charity good” than if 99% of people have internalized nostrums like “socialism good, civility bad, law enforcement bad, looting good.”10 You can try to imagine a scenario where these two sets of moral values aren’t in direct conflict, but empirically those with the first set of moral values will favor an entrepreneurial society and those with the second set of values will not.11

-

History is how you develop compelling media. You can make up entirely fictional stories, of course. But even fiction frequently has some kind of historical antecedent. The Lord of the Rings drew on Medieval Europe, Spaghetti Westerns pulled from the Wild West, Bond movies were inspired by the Cold War, and so on. And certainly the legitimating stories for any political order will draw on history.

-

History is the true value of cryptocurrency. Bitcoin is worth hundreds of billions of dollars because it’s a cryptographically verifiable history of who holds what BTC. Read The Truth Machine for a book-length treatment of this concept.

-

History tells you who’s in charge. Why did Orwell say that he who controls the past controls the future, and that he who controls the present controls the past? Because history textbooks are written by the winners. They are authored, subtly or not, to tell a story of great triumph by the ruling establishment over its past enemies. The only history most people in the US know is 1776, 1865, 1945, and 1965 - a potted history of revolutions, world wars, and activist movements that lead ineluctably to the sunny uplands of greater political equality.12 It’s very similar to the history the Soviets taught their children, where all of the past was interpreted through the lens of class struggle, bringing Soviet citizens to the present day where they were inevitably progressing from the intermediate stage of socialism towards…communism! Chinese schoolchildren learn a similarly selective history where the (real) wrongs of the European colonialists and Japanese are centered, and those of Mao downplayed. And even any successful startup tells a founding story that sands off the rough edges.

In short, a history textbook gives you a hero’s journey that celebrates the triumph of its establishment authors against all odds. Even when a historical treatment covers ostensible victims, like Soviet textbooks covering the victimization of the proletariat, if you look carefully the ruling class that authors that treatment typically justifies itself as the champion of those victims. This is why one of the first acts of any conquering regime is to rewrite the textbooks (click those links), to tell you who’s in charge.

-

History determines your hiring policy. Why are tech companies being lectured by media corporations on “diversity”? Is it because those media corporations that are 20-30 points whiter than tech companies actually deeply care about this? Or is it because after the 2009-era collapse of print media revenue, media corporations struggled for a business model, found that certain words drove traffic, and then doubled down on that - boosting their stock price and bashing their competitors in the process?13 After all, if you know a bit more history, you’ll know that the New York Times Company (which originates so many of these jeremiads) is an organization where the controlling Ochs-Sulzberger family literally profited from slavery, blocked women from being publishers, excluded gays from the newsroom for decades, ran a succession process featuring only three cis straight white male cousins, and ended up with a publisher who just happened to be the son of the previous guy.14

Suppose you’re a founder. Once you know this history, and once all your friends and employees and investors know it, and once you know that no purportedly brave establishment media corporation would have ever informed you of it in quite those words15, you’re outside the matrix. You’ve mentally freed your organization. So long as you aren’t running a corporation based on hereditary nepotism where the current guy running the show inherits the company from his father’s father’s father’s father, you’re more diverse and democratic than the owners of The New York Times Company. You don’t need to take lectures from them, from anyone in their employ, or really from anyone in their social circle — which includes all establishment journalists. You now have the moral authority to hire who you need to hire, within the confines of the law, as SpaceX, Shopify, Kraken, and others are now doing. And that’s how a little knowledge of history restores control over your hiring policy.

-

History is how you debug our broken society. Many billions of dollars are spent on history in the engineering world. We don’t think about it that way, though. We call it doing a post-mortem, looking over the log files, maybe running a so-called time-travel debugger to get a reproducible bug. Once we find it, we might want to execute an undo, do a

git revert, restore from backup, or return to a previously known-good configuration.Think about what we’re saying: on a micro-scale, knowing the detailed past of the system allows us to figure out what had gone wrong. And being able to partially rewind the past to progress along a different branch (via a

git revert) empowers us to fix that wrongness. This doesn’t mean throwing away everything and returning to the caveman era of a blank git repository, as per either the caricatured traditionalist who wants to “turn back the clock” or the anarcho-primitivist who wants to end industrialized civilization. But it does mean rewinding a bit to then move forward along a different path16, because progress has both magnitude and direction. All these concepts apply to debugging situations at larger scale than companies — like societies, or countries.17

You now see why history is useful. A founder of a mere startup company can arguably scrape by without it, tacitly outsourcing the study of history to those who shape society’s laws and morality. But a president of a startup society cannot, because a new society involves moral, social, and legal innovation relative to the old one — and that requires a knowledge of history.

Why History is Crucial for Startup Societies

We’ve whetted the appetite with some specific examples of why history is useful in general. Now we’ll describe why it’s specifically useful for startup societies.

We begin by introducing an operationally useful set of tools for thinking about the past from a bottom-up and top-down perspective: history as written to the ledger, as opposed to history as written by the winners.

We use these tools to discuss the emergence of a new Leviathan, the Network, a contender for the most powerful force in the world, a true peer (and complement) to both God and the State as a mechanism for social organization.

And then we’ll bring it all together in the lead-up to the key concept of this chapter: the idea of the One Commandment, a historically-founded sociopolitical innovation that draws citizens to a startup society just as a technologically-based commercial innovation attracts customers to a startup company.

If a startup begins by identifying an economic problem in today’s market and presenting a technologically-informed solution to that problem in the form of a new company, a startup society begins by identifying a moral issue in today’s culture and presenting a historically-informed solution to that issue in the form of a new society.

Why Startup Societies Aren’t Solely About Technology

Wait, why does a startup society have to begin with a moral issue? And why does the solution to that moral issue need to be historically-informed? Can’t it just be a tech-focused community where people solve problems with equations? We’re interested in Mars and life extension, not dusty stories of defunct cities!

The quick answer comes from Paul Johnson at the 11:00 mark of this talk, where he notes that early America’s religious colonies succeeded at a higher rate than its for-profit colonies, because the former had a purpose. The slightly longer answer is that in a startup society, you’re not asking people to buy a product (which is an economic, individualistic pitch) but to join a community (which is a cultural, collective pitch). You’re arguing that the culture of your startup society is better than the surrounding culture; implicitly, that means there’s some moral deficit in the world that you’re fixing. History comes into play because you’ll need to (a) write a study of that moral deficit and (b) draw from the past to find alternative social arrangements where that moral deficit did not occur. Tech may be part of the solution, and calculations may well be involved, but the moment you write about any societal problem in depth you’ll find yourself writing a history of that problem.

For specifics, you can skip ahead to Examples of Parallel Societies — or you can suspend disbelief for a little bit, keep reading, and trust us that this historical/moral/ethical angle just might be the missing ingredient to build startup societies, which after all haven’t yet fully taken off in the modern world.

Applied History for Startup Societies

Here’s the outline of this chapter.

-

We start with bottom-up history. The section on Microhistory and Macrohistory bridges the gap between the trajectory of an isolated, reproducible system and the trajectories of millions of interacting human beings. Because both these small and large-scale trajectories can now be digitally recorded and quantified, this is history as written to the ledger — culminating in the cryptohistory of Bitcoin.

-

We next discuss top-down history. This is history as written by the winners, history as conceptualized by what Tyler Cowen calls the Base-Raters, history that justifies the current order and proclaims it stable and inevitable. It is a theory of Political Power vs. Technological Truth.

-

We then talk about the history of power, giving names to the forces we just described by identifying the three candidates for most powerful force in the world: God, State, and Network. Framing things in terms of three prime movers rather than one allows us to generalize beyond purely God-centered religions to understand the Leviathan-centered doctrines that implicitly underpin modern society.

-

We apply this to the history of power struggles. With the God/State/Network lens, we can understand the Blue/Red and Tech-vs-Media conflicts in a different way as a multi-sided struggle between People of God, People of the State, and People of the Network.

-

We go through how the People of the State have used their power to distort recent and distant history, and how the Network is newly rectifying this distortion in “If the News is Fake, Imagine History.”

-

Having shown the degree to which history has been distorted, and thereby displaced the (implicit) historical narrative in which the arc of history bends to the ineluctable victory of the US establishment18, we discuss several alternative theories of past and future in our section on Fragmentation, Frontier, Fourth Turning, and Future Is Our Past. These theses don’t describe a clean progressive victory on every axis, but instead a set of cycles, hairpin turns, and mirror images, a set of historical trajectories far more complex than the narrative of linear inevitability smuggled in through textbooks and mass media.

-

We next turn our attention to left and right, which are confusing concepts in a realigning time, in Left is the new Right is the new Left. Sorry! We can’t avoid politics anymore. Startup societies aren’t purely about technology. But please note that for the most part this section isn’t the same old pabulum around current events. We do contend that you need a theory of left and right to build a startup society, but that doesn’t mean just picking a side.

Why? While a political consumer has to pick one of a few party platforms off the menu, a political founder can do something different: ideology construction. To inform this, we’ll show how left and right have swapped sides through history, and how any successful mass movement has both a revolutionary left component and a ruling right component.

-

Finally, all of this builds up to the payoff: the One Commandment. Using the terminology we just introduced, we can rattle it off in a few paragraphs. (If the following is opaque in any way, read the chapter, then come back and re-read this part.)

If history is not pre-determined to bend in one direction, if the current establishment may experience dramatic disruption in the form of the Fragmentation and Fourth Turning, if its power actually arose from the expanding frontier rather than the expanding franchise, if history is somehow running in reverse as per the Future Is Our Past thesis, if the revolutionary and ruling classes are in fact switching sides, if the new Leviathan that is the Network is indeed rising above the State, and if the internal American conflicts can be seen not as policy disputes but as holy wars, as clashes of Leviathans…then the assumption of the Base-Raters that all will proceed as it always has is quite incorrect! But rather than admit this incorrectness, they’ll attempt to use political power to suppress technological truth.

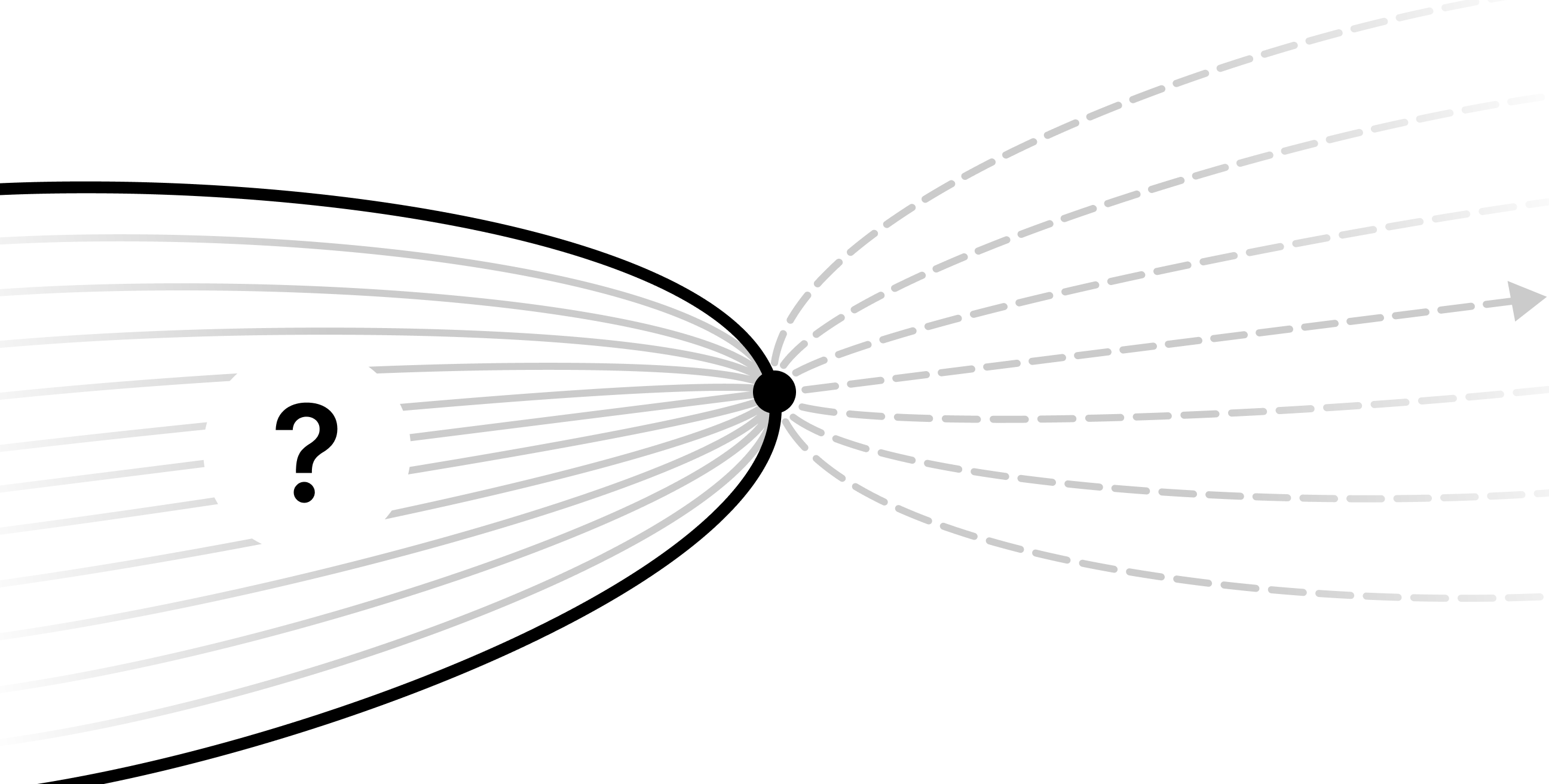

The founder’s counter is cryptohistory and the startup society. We now have a history no establishment can easily corrupt, the cryptographically verifiable history pioneered by Bitcoin and extended via crypto oracles. We also have a theory of historical feasibility, history as a trajectory rather than an inevitability, the idea that the desirable future will only occur if you put in individual effort. But what exactly is the nature of that desirable future?

After all, many groups differ with the old order but also with each other — so a blanket solution won’t work. And could well be resisted. That’s where the One Commandment comes in.

As context, the modern person is often morally reticent but politically evangelistic. They hesitate to talk about what is moral or immoral, because it’s not their place to say what’s right. Yet when it comes to politics, this diffidence is frequently replaced by overbearing confidence in how others must live, coupled with an enthusiasm for enforcing their beliefs at gunpoint if necessary.

In between this zero and ∞, in between eschewing moral discussion entirely and imposing a full-blown political doctrine, in this final section we propose a one: a one commandment. Start a new society with its own moral code, based on your study of history, and recruit people that agree with you to populate it.19 We’re not saying you need to come up with your own new Ten Commandments, mind you — but you do need One Commandment to establish the differentiation of a new startup society.

Concrete examples of possible One Commandments include “24/7 internet bad” (which leads to a Digital Sabbath society), or “carbs bad” (which leads to a Keto Kosher society), or “traditional Christianity good” (which leads to a Benedict Option society), or “life extension good” (which leads to a post-FDA society).

You might think these One Commandments sound either trivial or unrealistically ambitious, but in that respect they’re similar to tech; the pitch of “140 characters” sounded trivial and the pitch of “reusable rockets” seemed unrealistic, but those resulted in Twitter and SpaceX respectively. The One Commandment is also similar to tech in another respect: it focuses a startup society on a single moral innovation, just like a tech company is about a focused technoeconomic innovation.

That is, as we’ll see, each One Commandment-based startup society is premised on deconstructing the establishment’s history in one specific area, erecting a replacement narrative in its place with a new One Commandment, then proving the socioeconomic value of that One Commandment by using it to attract subscriber-citizens. For example, if you can attract 100k subscribers to your Keto Kosher society through deeply researched historical studies on the obesity epidemic, and then show that they’ve lost significant weight as a consequence, you’ve proven the establishment deeply wrong in a key area. That’ll either drive them to reform — or not reform, in which case you attract more citizens.

A key point is that we can apply all the techniques of startup companies to startup societies. Financing, attracting subscribers, calculating churn, doing customer support — there’s a playbook for all of that. It’s just Society-as-a-Service, the new SaaS.

In parallel, other startup societies are likewise critiquing by building, draining citizens away from the establishment with their own historically-informed One Commandments, and thereby driving change on other dimensions. Finally, different successful changes can be copied and merged together, such that the second generation of startup societies starts differentiating from the establishment by two, three, or N commandments. This is a vision for peaceful, parallelized, historically-driven reform of a broken society.

Ok! I know those last few paragraphs involved some heavy sledding, but come back and reread them after going through the chapter. The main point of our little preview here was to make the case that history is an applied subject — and that you can’t start a new society without it.

Without a genuine moral critique of the establishment, without an ideological root network supported by history, your new society is at best a fancy Starbucks lounge, a gated community that differs only in its amenities, a snack to be eaten by the establishment at its leisure, a soulless nullity with no direction save consumerism.20

But with such a critique — with the understanding that the establishment is morally wanting, with a focused articulation of how exactly it falls short, with a One Commandment that others can choose to follow, and with a vision of the historical past that underpins your new startup society much as a vision of the technological future underpins a new startup company — you’re well on your way.

You might even start to see a historical whitepaper floating in front of you, the scholarly critique that draws your first 100 subscribers, the founding document you publish to kick off your startup society.

Now let’s equip you with the tools to write it.

Next Section:

Microhistory and Macrohistory